By Sherry Mazzocchi

Wilhelmina Grant’s grandmother was the strong center of the family. A tall woman, she wore pants and sensible shoes and always had her handbag by her side, constantly holding the family’s purse strings.

But what Grant remembers most was her warmth and ability to heal. “Back in those days, we didn’t go to doctors,” said the Northern Manhattan-based artist. “In 1960’s segregated Sumter, South Carolina, getting sick meant finding a black doctor or seeking help within the family.”

Luckily, Fannie Grant knew what to do. Grant’s assemblage, La Curandera (The Healer), pays homage to her father’s mother.

The sparkling metallic work is fashioned from found objects, including bits of jewelry and part of a steamer. The result looks like an ethereal healing angel, someone equally adept at tending both broken bones and broken hearts.

Fannie Grant raised her children and six grandchildren. She had a big garden and a big heart. “People in the community would come to her for help,” said Grant. “She was also a political activist. She did everything.”

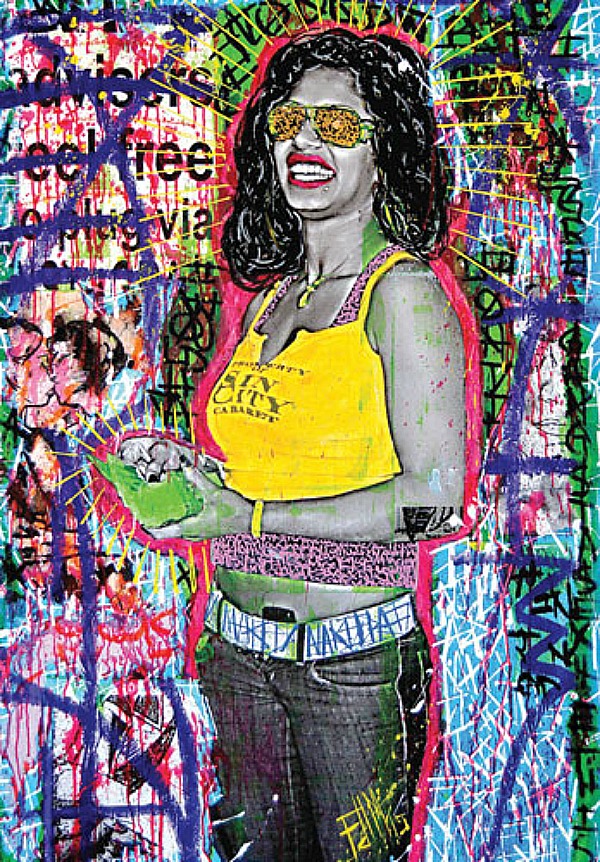

Grant’s work was one of several at NoMAA’s most recent show, “Women in the Heights—Resistance,” which closed last week.

“The times are so that we are seeing more political art, and we want to reflect that,” said Joanna Castro, NoMAA’s Executive Director. While female artists have as much as anyone to say about the current political climate, they often have fewer places to exhibit. “That is one of the main reasons we continue to have Women in the Heights.”

Read more: Rites of Resistance | Manhattan Times

We invite you to subscribe to the weekly Uptown Love newsletter, like our Facebook page and follow us on Twitter & Instagram or e-mail us at [email protected].