Photos & Story by: Amaris Castillo (@AmarisCastillo)

A bundled up Nisha Corniel emerged from the St. Frances Xavier Cabrini Shrine this past Sunday. It had been several years since she last attended Mass at the Washington Heights chapel, but tragic news has a way of pulling you back to your roots.

The 30-year-old wanted to squeeze in an extra prayer for Mother Cabrini High School, her alma mater.

Last week, news broke that the all-girls Catholic school would be closing its doors at the end of the 2013-2014 academic year. The announcement was posted on the school’s website and signed by both its president Bruce A. Segall and Board of Trustees chairperson Paula Greco-McTigue.

In tidy Arial font, the message pinned the planned closure on an economic downturn, declining enrollment and the growing costs of maintaining an old facility.

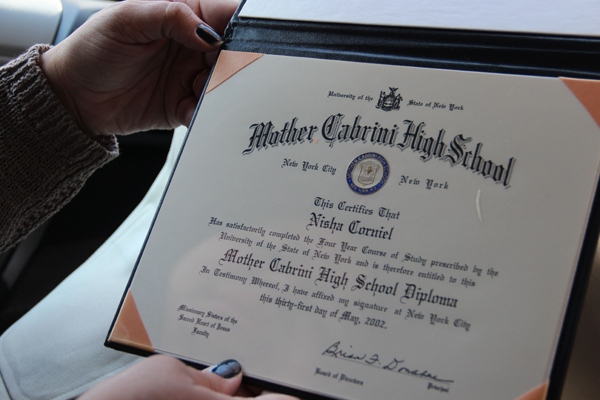

The news stunned the customer service professional at JPMorgan Chase, who graduated from the 115-year-old institution back in 2002. In response, current students and alumni have joined forces to try to help their ailing school.

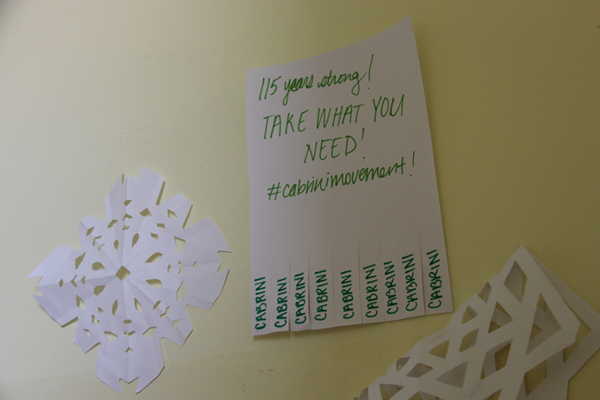

An Indiegogo campaign launched on Jan. 18 has since raised more than 28,000 dollars. A Facebook group was created for awareness, soon filled with heartfelt posts and encouragement. The supporters collectively call themselves “The Cabrini Movement.”

At the center of this fervor is a very special place. This school is where Corniel learned what sisterhood felt like – which held special meaning for the only child of Dominican immigrants. And now that the beloved school is in deep financial trouble, Corniel found herself yearning to share her story.

Corniel remembers having three high schools to choose from, but made up her mind after falling in love with Cabrini’s campus, which overlooks the Hudson River.

Corniel was at first wary about an all-girls environment, but she loved the idea of feeling “united” with others of the same sex.

“It actually built us a little stronger just because it’s a girlhood. You do your homework together, you’re in class together,” she said. “You have your girls to turn to.”

The absence of testosterone became a major pro.

“There wasn’t that competition of who looks better or ‘This guy’s here! That guy’s here,’” she added. “You didn’t have those issues in an all-girls school.”

Seated inside her parked car across the street from Mother Cabrini HS, Corniel reached behind her to pull out a bag filled with high school mementos. She admitted to crying as she recovered the items from storage in her Bronx home. Corniel still has her agendas – white spiral bound books covered in fun stickers and filled with homework assignments and tasks to complete. She took her time to leaf through the pages, reading her teenaged words and the codes she made up that her single mom couldn’t decipher. Inside worn photo albums were fuzzy photos of girls who impacted her life. She still talks to many of them.

In the photos, fresh-faced Latinas smiled in uniforms; they wore white shirts, plaid or blue skirts, and chose to stay warm in between navy blue and grey sweaters. Corniel and her friends would use a belt with their skirts and roll up the top to make them shorter. They hated how long they were.

And don’t get her started on the penny loafers – not cute.

As for teachers, there was the incredibly hot Mr. Murphy, who was also incredibly down-to-earth.

“We all wanted to take history just because of him,” Corniel added, her plump lips stretched into a giddy smile.

And who could forget Sister Mary Ellen, who was strict and showed her students what was expected of them.

“She taught us about the little things like your handwriting, your homework… your presentation,” she said. “You learned a lot.”

The expectations Cabrini teachers placed on their students were crystal clear.

“You were never treated like a kid – you were treated like a young lady,” Corniel emphasized. “You had things to do and they helped you discover talents that you didn’t even know you had. There were so many things that you could do and be successful at. And we all praised each other.”

Corniel’s father died when she was 8, and from that point on, she and her mom continued to push forward together. Her mom worked all the time, and a teenage Corniel kept busy at her private school.

“It was my refuge – not only because of the girls, but because of everything else,” she said. There were too many activities to list here; the well respected drum corps and choir, sports teams, even a Multicultural Society. The choir, made up of about 50 girls, was the best experience for Corniel. She also practiced volleyball, but wasn’t very good at it.

After some time, Corniel re-entered her old school. She walked through the first floor hallway with ease. The building’s pale yellow walls were livened through framed positive affirmations and photos of classes that have long since moved on. Corniel’s freckled face lit up when she came across a photo of her senior class to her right. She stood before it, searching for her friends and herself.

Corniel then led the way to a flight of stairs and began to climb up gingerly, peering up as if expecting someone from her past to come barging down. She reached the third floor, which looked as though it hadn’t been touched in a long time. In one sun-lit room, metal chairs from a forgotten era were scattered in no particular order. In another, one single chair and table were left behind. No chalk marks remained on any blackboards. Corniel stood in another empty room – what used to be her English classroom. The sadness on her face was interrupted a few times by spurts of happiness as she recalled the fond memories created within these walls.

She didn’t feel the school’s aging when she was a student, but she did now.

“Its sad because I wish that such a good school would look a little bit more up-to-date for the girls now. Now it’s a different time and a different set of girls,” she said. “I know our experience isn’t going to be the same as theirs and they need an up-to-date school. They need something to be proud of as well.”

Back at the chapel, Corniel peeled off her coat and settled into a pew by the front, where Mother Cabrini’s remains are interred in a tomb. Corniel’s eyes remained fixed on her saint.

“I feel like I’m connected again to what I used to be,” she whispered. “It’s like you have a family to come back to. Not even that – it’s just what they teach you… the values and sisterhood, and how to survive and be a strong woman. And that’s what she [Cabrini] was.”

Corniel and her fellow Cabrinians are not going down without fighting for their mutual treasure.

“We do not give up. You can’t give up,” she said. “You have to try, and that’s what Mother Cabrini did. She tried; she built a school for immigrants so they can be something – so they can have a shot to be somebody.”

Is Corniel somebody?

“I definitely am,” she said. Very strong.

“And it’s mostly because of what I was taught here.”

Support here: http://indiegogo.com/projects/save-mother-cabrini-high-school

Amaris Castillo is a multi-media journalist, check her out at http://amariscastillo.com and follow her on Twitter via: @AmarisCastillo.

Check out:

Sonia Manzano reminds East Harlem of the Young Lords Party with new book

Uptown Portrait: Natividad (“Dora the Explorer”)

Her Gems: An East Harlem Dollmaker’s Tale

We invite you to subscribe to the weekly Uptown Love newsletter, like our Facebook page and follow us on Twitter, or e-mail us at [email protected].

Holding Onto Mother Cabrini | Amaris Castillo

February 24, 2015 at 9:55 am[…] (This story originally appeared in the Bradenton Herald) […]